By Ashrafuddin Pirzada

We are a nation plagued by division and discord in almost every sphere of life, and calling such a disjointed crowd a “nation” is an insult to the term. The social fabric is torn apart by mistrust, political polarization and violence. Nowhere is this more visible than in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, where terrorist incidents have once again surged. In both provinces, security forces have made invaluable sacrifices, often at the cost of their own lives, to hold the line against militancy. Yet these sacrifices have not brought the decisive and permanent peace that Pakistan so urgently needs.

Today, the country is fighting a long, exhausting, nerve-wracking war against an enemy that refuses to relent. This is not a conventional battle fought on clear frontlines but a shadow war of infiltration, ambushes and calculated terror. Our soldiers have blocked the enemy’s advance, but at a heavy cost in lives and national morale. While the military response has been necessary, defence experts believe it cannot be the sole pillar of a lasting peace strategy. The authorities, they argue, must explore other viable options before the conflict consumes yet another decade.

When it comes to eliminating terrorism, especially in the merged tribal districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the Pashtun population stands divided into two extreme camps. The presence of large numbers of banned outfit members and their local facilitators has not only disrupted daily life in these districts, especially in Khyber, Bajaur and Waziristan, but also spilled over into neighbouring settled areas. Militants have repeatedly challenged the state’s writ, turning once-thriving towns into zones of fear and uncertainty. These are no longer poorly armed insurgents, but they now possess weapons as modern and lethal as those carried by our own forces and police.

From a military standpoint, officials stress that any decisive operation would require the displacement of large sections of the civilian population. Keeping civilians in active operational zones hampers effectiveness and risks tragic casualties. Yet for the people of the tribal belt, displacement carries bitter memories from the past as towns emptied of their residents, homes reduced to rubble, livelihoods destroyed and years spent in tented camps with little more than hollow promises of rehabilitation.

One side of the divide insists on an all-out military operation, arguing that half-measures have failed before and that only uncompromising force can dismantle militant networks. The other side is equally adamant in opposition, seeing military action as a recipe for mass suffering, economic collapse and another lost decade. They point to past operations that couldn’t be completely successful to fully eradicating terrorism while leaving tens of thousands still struggling to rebuild their lives more than a decade later.

The harsh reality is that complete opposition to military action is dangerously unrealistic. If terrorists are entrenched in fortified hideouts across the merged and southern districts, armed to the teeth, capable of striking at will and undermining state authority with impunity, then doing nothing amounts to surrender.

If the military refrains from acting merely to avoid displacement, the consequences could be catastrophic as unchallenged militant rule, targeted killings of not only military personnel and police but also civil servants, journalists and social workers, mass extortion and the collapse of normal life. In such a scenario, who will safeguard the lives, property and dignity of the people?

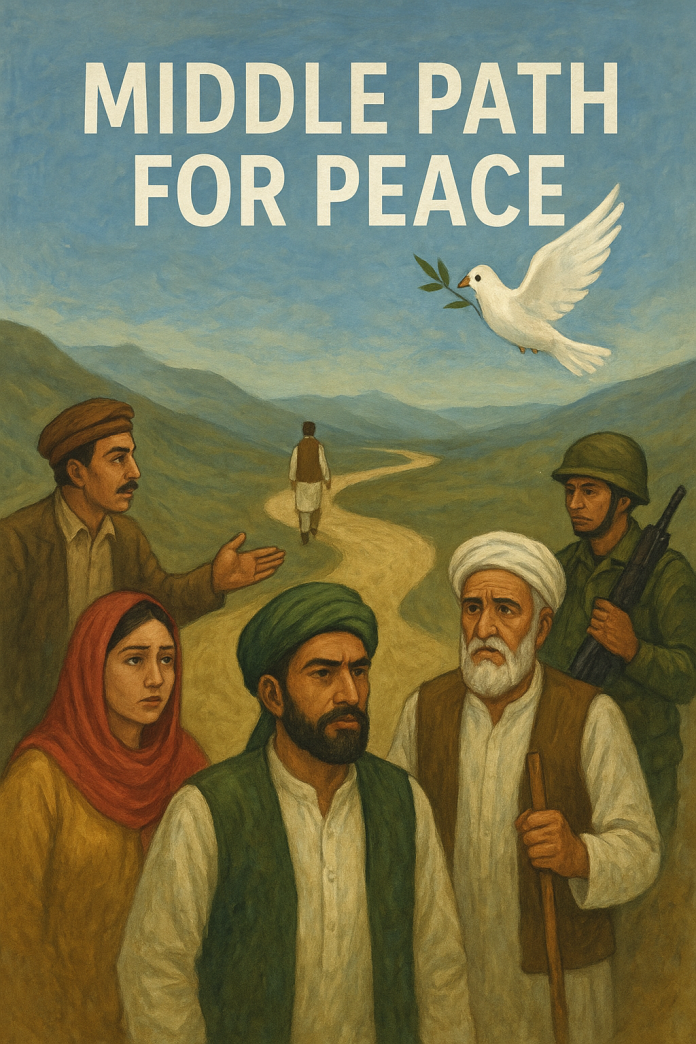

Both extremes, immediate all-out war or total inaction, are impractical in the current climate. Each risks causing more harm than good.

Between them lies the only viable way forward. A middle path that secures the state while protecting the people. This path begins with genuine, empowered negotiations led by a credible jirga of tribal elders, political leaders and business representatives, with full backing from both provincial and federal governments. Such a jirga should have real decision-making authority and travel to Kabul to meet with TTP leaders in the presence of Afghan officials as guarantors. The jirga would listen to militant demands, accept those that are reasonable and put forward its own conditions.

Even if complete success is not achieved in the first meeting, subsequent rounds could yield progress. Past suggestions by the Afghan government, such as relocating Pakistani militants to Afghanistan’s western and northern provincesdeserve renewed consideration.

Negotiations would also serve another purpose of proving to all sides that every peaceful avenue was explored before military action. If talks fail, the state would have both the political and moral grounds for decisive force.

Alongside this, the jirga system itself must be strengthened in the merged districts to serve as a permanent mediator between the state